Battle of Mistick Fort – The Withdrawal

Battle of Mistick Fort:

English Withdrawal and Pequot Counterattacks

In July 2011 the Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center (MPMRC) was awarded a new National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program (NPS ABPP) grant (GA-2255-11-011) designed to document the English-Native allied forces’ six-mile western withdrawal route following the destruction of Mistick Fort on the morning of May 26, 1637.

The “Battle of Mistick Fort: English Withdrawal and Pequot Counterattacks” constitutes the second phase of the Battle of Mistick Fort (May 25-26, 1637). The Battle of the English Withdrawal began on May 26, 1637 near 9 a.m. approximately two hours after the Mistick Fort Battle (the attack and destruction of the Pequot fortified village) (Site 59-19). The withdrawal consisted of near ten hours of intense fighting between English allied and Pequot forces over a four-mile stretch of difficult terrain.

This phase of the Battle of Mistick Fort was the largest combat action of the entire war and the longest period of fighting during the Mistick Campaign with more than 600 combatants engaged over hundreds of acres. The English reported that they killed more Pequot during their withdrawal than at the Mistick Fort Battle, and by 7 p.m. on May 26, the Pequot had perhaps lost half of their fighting men. The loss of 400-500 Pequot during the Mistick Campaign was a devastating blow to the Pequot and the turning point of the war. The following is a brief history of the encounter:

Battle of the English Withdrawal (9:00 a.m. – 7:00 p.m., May 26, 1637)

The Battle of the English Withdrawal began shortly after the English spotted their ships sailing through Long Island Sound. After the English saw their ships sailing through Long Island Sound they formed a column, with Captain Mason at the front and Captain Underhill at the rear and began their march west.

English-allied forces had already marched 35 miles and fought a major battle on very little rest. They were low on rations and ammunition, and sustained heavy casualties during the Mistick Fort battle (30% or more of the English contingent; unknown number of Native allies). With an effective fighting force of only 60 English, the allied force now faced an experienced and determined Pequot opponent. Hundreds of Pequot fighting men were now mobilized from other villages and converging on the battlefield.

The first Pequot counterattack of the Withdrawal, occurred just as the English began their march towards Pequot harbor (present day Thames River harbor). Captain John Mason states the attack consisted of around 300 men from the other fortified village at Weinshauks. Mason’s narrative briefly describes the third and final attack on the western slope of Pequot Hill:

We had no sooner discovered our Vessels, but immediately came up the Enemy from the other fort; Three Hundred or more as we conceived. The Captain lead out a File or two of Men to Skirmish with them, chiefly to try what Temper they were of, who put them to a stand: we being much encouraged thereat, presently prepared to March towards our Vessels: Four or Five of our Men were so wounded that they must be carried with the Arms of twenty more. We also being faint, were constrained to put four to one Man, with the Arms of the rest that were wounded to others; so that we had not above forty Men free: at length we hired several Indians, who eased us of that Burthen in carrying of our wounded Men.[1]

After the English checked this initial counterattack, the Pequot withdrew to the south some distance from the English (at least out of musket range). As the English began their withdrawal and vacated Pequot Hill the Pequot circumvented them and made their way to the summit of Pequot Hill where they saw the remains of the burned Mistick Fort and 400 of their dead kinsmen. The allied column was one-quarter mile down the western slope of Pequot Hill when the 300 Pequot men launched a furious assault from the burned fort:

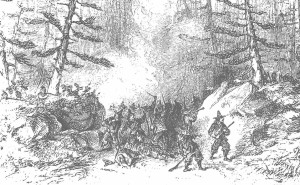

And Marching about one quarter of a Mile; the Enemy coming up to the Place where the Fort was, and beholding what was done, stamped and tore the Hair from their Heads: And after a little space, came mounting down the Hill upon us, in a full career, as if they would over run us; But when they came within Shot, the Rear faced about, giving Fire upon them: Some of them being Shot, made the rest more wary: Yet they held on running to and fro, and shooting their Arrows at Random.[2]

The Pequot attacked the rear of the English allied column, one-quarter of a mile west from the summit of Pequot Hill. Mason, at the head of the column, was probably several hundred yards further away and perhaps had already reached a small stream at the base of Pequot Hill. As the English described the terrain as “champion [open] country”, they were had time to prepare their defense against the in-view Pequot who mounted their attack down Pequot Hill. The rear of the column, led by Underhill, “with divers Indians and certain English issued out to encounter them” turned and fired several volleys into the charging Pequot which broke the attack.”[3]

No historical evidence exists on the arrangement or in with respect to how English and Native allies were deployed. It is reasonable to infer that the English, with longer ranged weapons, were placed along the outer edge of the column while their Native allies formed in the interior of the column (as well as the wounded). This prevented the Pequot from penetrating the column and if need be sallying out to engage the Pequot at close quarters. Mason alludes to this when he recounts: “But when any of them [Pequot] fell, our Indians would give a great Shout, and then would they take so much Courage as to fetch their Heads.”[4]

Unlike previous engagements, the Pequot did not withdraw after an initial the English initial volley. They used the terrain to their advantage and continued to assault the English allied column by maneuvering and attacking the formation from the flanks and rear and setting ambushes at the front of the column:

yet some of them lay in Ambush behind Rocks and Trees, often shooting at us, yet through Mercy touched not one of us: And as we came to any Swamp or Thicket, we made some Shot to clear the Passage. Some of them fell with our Shot; and probably more might, but for want of Munition.[5]

For their part the Pequot seemed to have abandoned the tactics that had proven so successful against the English in the first six months of the Pequot War prior to Mistick. Although the Pequot did try and lure or drive the English into ambush points along the way in order to fire their arrows at point blank range (generally less than 30 yards), they were so enraged by the deaths of more than 400 of their people at Mistick they would often venture themselves in the open.

One of the major concerns of English commanders was their dwindling supply of ammunition, already depleted after the Mistick Fort battle. This supply diminished further as the English fought off constant Pequot attacks. To counter Pequot ambushes from the thickets and swamps along the route of withdrawal, the English would fire a preemptory volley to clear the way. Mason recounted “Some of them fell with our Shot; and probably more might, but for want of Munition.”[6] On another occasion states “I was somewhat cautious in bestowing many shot upon them needlessly, because I expected a strong opposition.”[7] If the English were trying to conserve their ammunition, then they may have only fired on the Pequot when the opportunity presented itself, as recounted by Underhill:

One Sergeant Davis, a pretty courageous souldier, spying something black upon the toppe of a rock, stepped forth from the body with a Carbine of three foot long, and at a venture gave fire, supposing it to bee an Indians head, turning him over with his heeles upward; the Indians observed this, and greatly admired that a man should shoot so directly. The Pequeats were much daunted at the shot, and forbore approaching so neere upon us.”[8]

After the English allied force halted the Pequot attack midway down Pequot Hill, the column made a brief stop at a stream at the bottom of the hill (present day Fishtown Brook) “where we rested and refreshed ourselves, having by that time taught them a little more Manners than to disturb us.”[9] The English and Native allies likely established defensive positions on the high ground to the east overlooking the stream which provided excellent views of the surrounding terrain to the east and west of the stream.

As Mason led the allied force west from Fishtown Brook toward the Thames River they faced constant attacks from the front, rear, and flanks of the column. Shortly after the column left Fishtown Brook Mason recounted “We then Marched on towards Pequot Harbour; and falling upon several Wigwams, burnt them: The Enemy still following us in the Rear … yet some of them lay in Ambush behind Rocks and Trees, often shooting at us, yet through Mercy touched not one of us: And as we came to any Swamp or Thicket, we made some Shot to clear the Passage.”[10]

The English fought off Pequot attacks for the remainder of the three mile withdrawal ending only when the English allied forces were within two miles of Pequot Harbor (present-day Pequannock Bridge, Groton, CT):

some of them lay in Ambush behind Rocks and Trees, often shooting at us, yet through Mercy touched not one of us: And as we came to any Swamp or Thicket, we made some Shot to clear the Passage. Some of them fell with our Shot; and probably more might, but for want of Munition: But when any of them fell, our Indians would give a great Shout, and then would they take so much Courage as to fetch their Heads. And thus we continued, until we came within two Miles of Pequot Harbour; where the Enemy gathered together and left us: we Marching on to the Top of an Hill adjoining to the Harbour, with our Colours flying.[11]

The army was ferried to the west bank of the Thames and disembarked to spend the night on shore near their ships while the other vessels transported the wounded to Saybrook Fort. The next morning Mason and his remaining allied forces marched twenty miles through Western Niantic territory reaching the east bank of the Connecticut River the evening of May 27, 1637. The English allied force encamped along the Connecticut River for the night and in the morning were transported over the river and to the safety of Saybrook Fort. The Mistick Campaign was over.

“A Pink, a pinnace, and a shallop” were the three watercraft used by English-Allied forces during the Mistick Fort Campaign.

Footnotes:

[1] Vincent, A True Relation. P. 11.

[2] Mason, History of the Pequot War. P. 11

[3] Mason in Hubbard, History of the Pequot War. P. 127

[4] Underhill, Newes From America, P. 19.

[5] Mason, History of the Pequot War. P. 11.

[6] Mason, History of the Pequot War. P. 11.

[7] Mason, History of the Pequot War. P. 12.

[8] Mason, History of the Pequot War. P. 12.

[10] Mason, History of the Pequot War. P. 11.

[11] Mason, History of the Pequot War. P. 12.