The Pequot War

The History of the Pequot War

Prelude to War

Before the Pequot War (1636-1637), Pequot territory was approximately 250 square miles in southeastern Connecticut. Today, this area includes the towns of Groton, Ledyard, Stonington, North Stonington and southern parts of Preston and Griswold. The Thames and Pawcatuck Rivers formed the western and eastern boundaries, Long Island Sound the southern boundary and Preston and Griswold (southern parts) the northern boundary. Some historic sources suggest that Pequot territory extended four to five miles east of the Pawcatuck River to an area called Weekapaug in Charlestown, Rhode Island prior to the Pequot War.

Within this territory during the early 17th century lived some 8,000 Pequot men, women and children (4,000 after the smallpox epidemics of 1633-1634), residing in 15-20 villages of between 50 to 400 people before the war. These villages were located along the estuaries of the Thames, Mystic and Pawcatuck Rivers and along Long Island Sound.

A Volatile Situation

The Pequot War is best understood through examining the broader cultural, political and economic changes that occurred following the arrival of the Dutch in 1611 and English in the early 1630’s.

To control the fur and wampum trade during the 1620’s, the Pequot attempted to subjugate other tribes throughout Connecticut and the islands offshore. By 1635, the Pequot had extended their control through a tributary confederacy of dozens of tribes created through coercion, warfare, diplomacy and intermarriage.

For a time, the Dutch and Pequot controlled all trade in the region which resulted in short-term stability, though potentially volatile situation, as many Native tribes were resentful of their tributary status to the Pequot. The arrival of English traders and settlers in the Connecticut River Valley in the early 1630’s shifted the balance.

The arrival of the English in the Connecticut River Valley resulted in intense competition and conflict for control of trade and tribes wrested themselves from Pequot subjugation – resulting in the outbreak of the Pequot War.

Causes of the Pequot War

The primary cause of the Pequot War was the struggle to control trade. English efforts were to break the Dutch-Pequot control of the fur and wampum trade, while the Pequot attempted to maintain their political and economic dominance in the region.

Particular events which have often been cited as the cause for the Pequot War are the murders of English traders. However, these deaths were the culmination of decades of conflict between Native tribes in the region, further amplified by the arrival of the Dutch and English.

Trader John Stone and his crew in the Connecticut River were murdered by the Pequot in the summer of 1634. Although the Pequot provided several explanations for Stone’s death, all of which suggested they viewed their actions as justified, the English felt they could not afford to let any English deaths at the hands of Natives go unpunished. As tensions grew between all parties, the murder of trader John Oldham by the Manisses Indians of Block Island in July, 1636 resulted in a military response by the English of Massachusetts Bay that led directly to the Pequot War, the first battlefield site defined as Battlefields of the Pequot War.

Endicott’s Raid on Manisses Villages

Block Island, Rhode Island

In late August 1636, Massachusetts Bay organized a force of 90 soldiers under the command of Colonel John Endicott. This group launched a punitive expedition against the Manisses of Block Island in retaliation for the murder of trader John Oldham (just a month earlier).

The force sailed from Boston on August 24, 1636 bound for Block Island with instructions to kill all the men and take away the women and children.

After a briefly contested amphibious landing along the east beaches of the Island (the first recorded amphibious assault in the New World), the expedition established a base camp what is now Crescent Beach. Base camp was near their point of landing and a short distance from their anchored ships.

The English spent two days searching the island for the Manisses, who fled into the swamps for safety. While a few Manisses warriors skirmished with the English, no significant action took place. The English burned five or six villages and destroyed several cornfields.

Before proceeding to the Pequot (Thames) River with instructions to take by force if necessary the murderers of John Stone and his crew, Endicott’s forces sailed to Saybrook Fort and discussed actions with Lieutenant Lion Gardiner and others. Several of Endicott’s and Gardiner’s men together sailed to Pequot country and disembarked on the east side of the Pequot (Thames) River at the site of a major Pequot village (possibly the present site of the United States Naval Submarine Base).

Negotiations were unsuccessful and the English landed and burned the village. One of the Native guides/interpreters who accompanied the English killed a Pequot “and thus began the war between the Indians and us (English) in these parts” (Gardiner 1901: 11). The Pequot viewed this action as an unprovoked attack and immediately began military operations against the English outpost at Saybrook Fort at the mouth of the Connecticut River.

Siege and Battle of Saybrook Fort

Saybrook Point (& surrounding areas),

Old Saybrook, Connecticut

The longest engagement of the Pequot War, and in retaliation for Endicott’s attack on the Manisses and Pequot villages, the Pequot laid siege to Saybrook Fort from September 1636 through mid-April 1637. The Pequot attacked soldiers and work parties who ventured too far from the fort, destroyed English cornfields and cattle, and burned warehouses used to store trade goods.

Early in September, English soldiers venturing from their blockhouse two miles south of Saybrook Fort were attacked by Pequot warriors, two of which were killed. Lieutenant Lion Gardiner evacuated the blockhouse and Pequot warriors burned the structure soon after, along with several English warehouses north of the fort (near present-day Ferry Point, Old Saybrook). Later that fall, three English settlers were killed and another captured as they gathered hay on an island north of the fort.

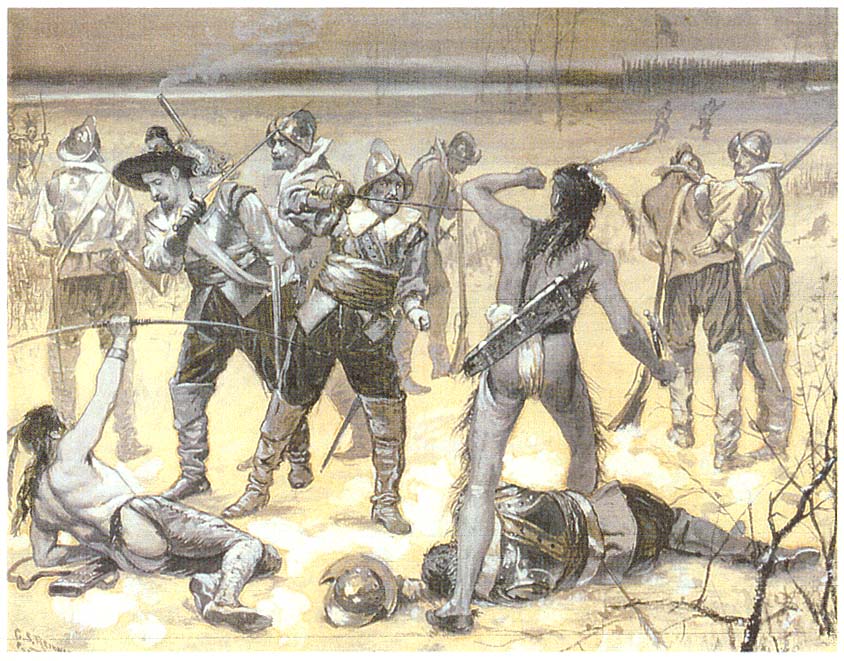

This 1890 watercolor by Charles Reinhart depicts Lieutenant Lion Gardiner and his forces clashing with Pequot warriors at Saybrook Fort.

On February 22, 1637 Lion Gardiner and twelve men ventured to Saybrook Neck to burn reeds when they were ambushed by approximately 100 Pequots. Four English soldiers were killed and another four were wounded.

Throughout the spring, Pequot warriors attempted to cut off all river traffic to and from the upriver Connecticut colonies of Hartford, Wethersfield and Windsor. At the same time, the Pequot pursued various diplomatic initiatives with neighboring tribes to enlist their aid against the English, including overtures to the Narragansett, their traditional enemies. This effort failed due to mistrust and years of warfare between the Pequot and Narragansett. The Narragansett then entered the Pequot War on the side of the English.

Attack on Wethersfield,

Banks of the Connecticut River

Wethersfield, Connecticut

On April 23, 1637 a large force of Pequot warriors attacked English settlers at Wethersfield on their way to their fields in the Great Meadow along the Connecticut River. The Pequot killed nine men and women and captured two girls who were brought to Pequot territory. The girls, later rescued by the Dutch, claimed the Pequot wanted to know how to make gunpowder.

Up until the events of the Attack on Wethersfield, the English in Connecticut did not believe they had “just” grounds to declare full scale war against the Pequot.

Connecticut First Declaration of War

May 1, 1637

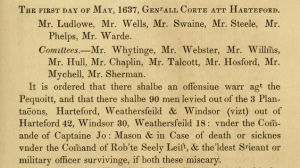

As a result of the Wethersfield attack, Connecticut declared war on the Pequot on May 1, 1637. The colony raised a force of ninety soldiers from the three river towns (Hartford, Wethersfield and Windsor) for an expedition against the Pequot. Captain John Mason of Windsor was given command of the Connecticut forces and issued instructions to attack the Pequot fortified villages at Mistick and Weinshauks (the home of Sassacus).

May 1 Declaration of the Pequot War. Page lifted from the “Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut” edited by J. H. Trumbull.

Mistick Fort Campaign

Mystic, Connecticut

The Mistick Fort Campaign is the most famous battle of the Pequot War. It is more commonly referred to by historians as the Massacre at Mystic.

PLAN AND APPROACH

During the first two weeks of May, 1637, men were levied from Windsor, Wethersfield and Hartford placed under the command of Captain John Mason. Meeting at Saybrook Fort, they were joined by Massachusetts Bay soldiers under the command of Captain John Underhill, along with Mohegan and Connecticut River Indian warriors under the Mohegan sachem Uncas. Together these allied English and Native troops (over 150 men) sailed in three vessels to Narragansett to join with the Narragansett in a combined effort against the Pequot.

The English arrived at Narragansett on May 18, 1637, and spent two days negotiating with the Narragansett sachems. On May 23, a force of approximately 80 English (10 remained with the ships), 60 Mohegan and River Indians under Uncas, and 200 Narragansett marched 30 miles to present-day Mystic, Connecticut. The extreme heat during the final miles of the march exhausted the English, and they decided to attack only Mistick Fort, the nearest and easternmost of the two Pequot fortified villages.

The English forded the Mystic River at dusk on May 25 and marched two miles to Porter’s Rocks where they made camp for the night. At dawn on May 26, the English and their Native allies approached the circular palisaded village at the top of Pequot Hill to begin the attack.

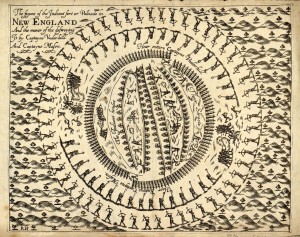

From Captain John Underhill, a woodcut print depicting a birds-eyes view of the Battle of Mistick Fort, May 1637.

BATTLE of MISTICK FORT

The English battle plan split their forces in order to gain entry to the fort simultaneously through entrances in the northeast and southwest entrances. Captain Mason’s 20 soldiers forced their way through an entrance in the northeast quadrant and encountered stiff resistance as their approach was heard alerting the Pequot within Mistick Fort.

The original battle plan was to “destroy them by the sword and save the plunder,” but the English entry was so hotly contested and the lanes between the rows of wigwams and lanes so narrow, the English could not effectively deploy their men (Mason in Prince 1736: 28). Within a few minutes after gaining a challenged entry to Mistick Fort the English suffered two dead and twenty wounded – 50% of the force that entered the fort.

“we should never kill them after that manner; the Captain [Mason] also said, We must burn them, and immediately stepping into a wigwam where he had been before, brought out a firebrand, and putting it into the matts with which they were covered, set the wigwams on fire” (Mason in Prince, 1736: 28-29).

Within minutes, Mistick Fort was engulfed in fire fanned by a stiff northeast wind. The English retreated and encircled the fort to prevent anyone from escaping, while firing into the fort at anyone who attempted to escape. The Mohegan and Narragansett formed an outer ring preventing further escape of Pequot who slipped through the English line.

In one hour, more than 400 Pequot men, women and children were killed. The English reported only seven Pequot were captured and seven escaped.

ENGLISH REST AND VANTAGE POINT,

AND PEQUOT COUNTERATTACKS

After the battle at Mistick Fort, the English and their Native Allies were exhausted, not only physically, but also in supplies and ammunition. The situation presented to them (exhausted of necessaries and in enemy territory) was not good. The English suffered over 50% causalities (men killed and wounded) during the course of the battle. Men who were severely wounded were carried after the battle. Mohegan, River Indian and Narragansett casualties are unknown, although one account identified forty Native casualties and another described several Narragansett killed by the English who mistook them for Pequot.

“And thereupon grew many difficulties: Our provisions and munition near spent; we in the enemies country, who did far exceed us in number, being much inraged: all our Indians, except Onkos, deserting us; our pinnaces at a great distance from us, and when they would come we were uncertain.” (Mason in Prince 1736: 11)

The English and their Native allies established a temporary camp just to the south of the Mistick Fort to gain a view of Long Island Sound. The English ships were intended to meet the force in the Pequot (Thames) River and carry them to the safety of Saybrook Fort. As the ships had not yet seen been from Pequot Hill, the English were unsure how to proceed.

Shortly after the camp was established, hundreds of Pequot warriors from nearby villages mounted a series of counterattacks against the English allied forces still waiting on Pequot Hill. Captain John Underhill with 14 soldiers and an unknown number of Native allies advanced a short distance to meet the first counterattack. The Pequot would not venture within range of the English guns, and Underhill ordered the Mohegan and Narragansett to continue the fight so the English could observe Native combat. After a short time, Underhill returned to the main body still positioned on Pequot Hill just south of the destroyed fort.

A group of fifty Narragansett warriors, fearing the English were critically low on ammunition and unable to defend them against future Pequot counterattacks, left the group to ford the Mystic River and head east to the safety of Narragansett country. Not far from base camp, they were attacked by Pequot warriors from villages on the east side of the Mystic River. A runner returned to Mason and Underhill seeking assistance, and in response Underhill with 30 soldiers aided the Narragansett and battled the Pequot for an hour. Meanwhile, Captain John Mason waited with the wounded and awaited their return.

ENGLISH RETREAT THROUGH PEQUOT COUNTRY

Shortly after Underhill’s return, the English spotted their ships in Long Island Sound sailing west for the Pequot (Thames) River. As the troops retreated west to meet their ships, they were attacked by Pequots at the base of Pequot Hill. The Pequot rushed headlong down the hill and a furious battle ensued until the Pequot broke off the engagement.

The English allied forces stopped briefly at a stream at the base of Pequot Hill (Fishtown Brook) to refresh themselves and tend the wounded, and then they began an eight mile march to Pequot (Thames) River with Captain Mason at the head of the column (with the wounded) and Captain Underhill at the rear. This force was ambushed during their avenue of retreat as the Pequot fired at them from swamps and boulders. As a countermeasure, the English fired volleys into the swamps and thickets they encountered along the way. Underhill and the rear guard also faced constant attack from the flanks and rear. Underhill reported more Pequot warriors were killed in these actions than at Mistick Fort. The English lost one killed and several more wounded during the retreat. Native allied casualties are unknown.

The English encountered a small hamlet of several wigwams which they burned, but not before salvaging mats and poles to fashion stretchers for the four or five English wounded unable to walk, “some of them with the heads of the arrows in their bodies” (Trumbull 1765: 24). The Pequot counterattacks inexplicably stopped two miles from Pequot (Thames) River, perhaps because they had lost so many warriors in the counterattacks. The English marched to the top of a hill overlooking the river “with our colours flying” and saw their vessels at anchor (Mason in Prince 1736: 12).

Underhill, the wounded English, and some Native allies went aboard the English ships and sailed to Saybrook Fort. Mason and the remaining English and most of their Native allies stayed the night on the western shore of the river. The next morning, the force marched 20 miles to the Connecticut River. They arrived in the early evening, stayed the night, and were transported across the river to Saybrook Fort in the morning. Along the way, the force burned several wigwams and captured 10 warriors and eight women. Six of the warriors were executed “the other four given to as many sachems, one to each” (Trumbull 1765: 25). Four of the women remained at the fort and the other four transported up river to the Connecticut river towns. A dispute arose among the English and Native allies regarding the disposition of the women which the English resolved by executing them (Trumbull 1765: 25).

Pequot Abandon Their Territory

English & Native Allies Pursue Pequots

In the weeks following the destruction of Mistick Fort the remaining Pequot villages (estimated at 18-20 communities and 3,500 people) abandoned their territory for fear of additional attacks by the English. Many Pequot sought refuge among the Narragansett, Montauk and other Native tribes in the region fleeing the English. Sassacus and Mononnotto, the remaining chief sachems, elected to continue the fight against the English and Narragansett. Sassacus reportedly burned Weinshauks before he abandoned Pequot territory to seek allies and support to continue the fight against the English and Narragansett. Sassacus, with five or six sachems and perhaps two hundred men, women, and children, made their way west along the Connecticut coast intending to seek refuge and support from their allies and tributaries at Quinnipiac (New Haven) and Sasqua (Fairfield).

Battle of the Northeast

A large group of Pequot warriors under the sachem Mononotto went north to continue the fight against the Narragansett and join with the Wunnashowatuckoogs, a Nipmuc band in east-central Connecticut who were allies and tributaries of the Pequotato. In June of 1637 a major battle took place somewhere in east-central Connecticut between the Pequot/Wunnashowatuckoogs and the Narragansett and their Nipmuc allies/tributaries in one of the few recorded Native-Native battles of the Pequot War. The Pequot were defeated and Mononotto fled west along the Connecticut coast to join Sassacus at Sasquanikut (Fairfield).

Quinnipiac Campaign

Pequot Swamp Fight

Fairfield, Connecticut

PLAN AND APPROACH

It was not until late June and early July that the English organized another campaign against the remaining Pequot. This force consisted of 100 English soldiers and an unknown number of Native (Narragansett/Mohegan/Montauk) allies embarked from Saybrook Fort. The forces first sailed for Long Island in pursuit of Sassacus. The Montauk, once allies and Pequot tributaries, submitted to English authority and relayed that Sassacus was at Quinnipiac (New Haven). The English force disembarked at present day Guilford, and executed three Pequot sachems they captured at a neck of land known today as Sachems Head. The English continued on to Quinnipiac to learn that Sassacus, who had been informed of their approach, escaped to Sasquanikut (Fairfield), home of their allies and tributaries the Sasqua. The English force continued on foot to the Housatonic River, encountering scattered groups of Pequots along the way. After crossing the Housatonic River with assistance from their vessels, the English eventually caught up with Sassacus’ group at Sasquanikut where the last major battle of the Pequot War took place (Fairfield Swamp Fight) on July 13-14, 1637 at Munnacommuck Swamp, known today as the Pequot Swamp.

The English force of approximately 100 soldiers and Indian allies forded the Mill River and proceeded southwest along Mill Hill which provided a commanding view of the area to the south and west. At the southwest tip of the hill the English observed the Pequot and their Sasqua allies in a village on the far side of the swamp less than two miles away. The Pequot and Sasqua spotted the English at the same time and fled into the swamp for safety.

SWAMP FIGHT

The English marched to the base of the hill and continuing on, they encircled the swamp which was approximately one-mile in circumference. Following several hours of combat the English allowed the women and children to surrender with promises to spare their lives (all were sold into slavery either in the Caribbean or New England colonies). The English force of 100 soldiers was not sufficient to prevent Pequot warriors from escaping the swamp and they proceeded to cut the swamp in half to more effectively surround it and contain the remaining warriors inside. What followed was a 24-hour battle that was one of the fiercest of the war, and one of the only battles where Pequot warriors were reported to have used firearms against the English. Hand-to-hand fighting took place throughout the day and night as the English tried to gain entry into the swamp and Pequot warriors attempted to escape. On the morning of July 14, under cover of fog, approximately 60-80 Pequot warriors broke through a section of the English lines and escaped, although many were wounded and killed in the attempt. English accounts of Pequot casualties differ, ranging from seven dead to as many as 60.

Capture of Sassacus, Pequot Sachem

Dover Plains, New York

Hours before the English reached Munnacommuck Swamp, Sassacus, with six sachems, a few women (perhaps Sassacus’ daughter) and a body guard of 20 warriors fled north up the Housatonic River and west up the Ten Mile River into eastern New York with the intention of reaching Mohawk territory near Albany, New York to enlist their aid against the English. The Pequot were discovered by a contingent of Mahican or Mohegan (the primary sources are not entirely clear) and Mohawk warriors near the “Stone Church” in Dover Plains, New York. Following a brief skirmish, Sassacus’ group made their way to Paquaige in late July (west of Danbury, CT) where they were surprised in their wigwams by the Mohegan and Mohawk. Sassacus was killed immediately and the few Pequot who managed to escape were quickly found and executed. The Mohawk sent the “locks” to Agawam (Springfield) and Hartford, reaching Boston on August 5, 1637 effectively ending all Pequot resistance.

Last Action: Block Island

The Pequot War ended where it began, on Block Island. On August 1, 1637 Israel Stoughton pursued refugee bands of Pequot, and sailed to Block Island with a small force to seek satisfaction from the Manisses. Stoughton and his men killed several Manisses and burned several wigwams before the Manisses submitted to English authority.

The Hartford Treaty

The Treaty of Hartford ratified by the English, Mohegan and Narragansett on September 21, 1638 was the official end to the Pequot War. The treaty stipulated that the surviving Pequot were to be dispersed among the Mohegan and Narragansett, and no longer to be called Pequot. The treaty also stipulated that the surviving Pequot would never be allowed to live in their former territory.